Transparency is Critical in Contracts and Supply Chain

Authors: Rob Handfield and Dan Finkenstadt

The Defense Acquisition University has joined forces with the National Contract Management Association (NCMA) as the Department of Defense (DOD) adopts NCMA’s Contract Management Standard™ (CMS™).

The 2020 National Defense Authorization Act[1] directs defense agencies to align government and commercial acquisition workforce development criteria to industry standards. Thus, the Defense Acquisition University has joined forces with the National Contract Management Association (NCMA) as the Department of Defense (DOD) adopts NCMA’s Contract Management Standard™ (CMS™).[2] The CMS™ requires that contract managers understand supply chain management principles. Given our recent experiences working with and advising on COVID-19 supply chain task forces at the federal, state, and local levels, we could not agree more.

Our perspectives have been formed through a combined 60 years of experience in supply chains, business operations, military operations, federal acquisitions, and academic research. Daniel Finkenstadt is a 20-year U.S. Air Force officer and professor with more than 17 years of contracting experience at all levels from air base supplies to the Pentagon staff. Rob Handfield, a prolific consultant, professor, author, and thought leader in the realm of advanced supply chain management, studies the intersection of public and private value chains.

Our experiences afford us unique opportunities to network with thought leaders in other areas of public and private business and policy. We hope to leverage these experiences and networks to bring you the best in contemporary, novel, and sometimes provocative ideas and actionable advice. (Full transparency: We also are likely to offer ideas that you might find ill-informed or incomplete. Good! If you use this column as a catalyst to provide a better position, idea, or tool, then we have more than met our intent.)

Speaking of transparency, let’s get into our first topic: transparency in contract management and supply chains. Transparency is one of the three primary objectives of public procurement (along with value and meeting requirements in a timely fashion). It is the instrument of public trust that we employ most often in contract management. Everything we do—from market research interactions to post-award debriefings—is keenly focused on being as transparent and fair as possible when allocating public funds. Private firms that understand strong supplier relationship management techniques also attempt to transparently apportion information to their vendors while balancing competitive tensions.

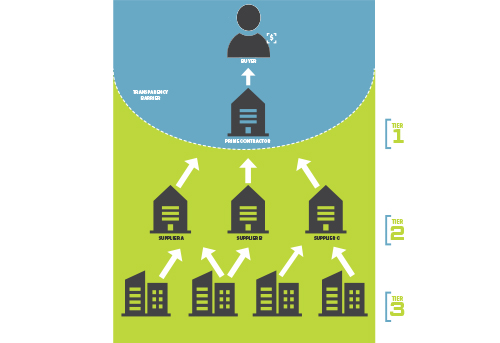

Unfortunately, in most supply chains, transparency extends only to prime contractors in the first tier. Rarely do firms or agencies have transparency into Tier 2 or Tier 3 suppliers or beyond, which is where the biggest problems often occur. (Refer to FIGURE 1.) Human rights violations, capacity bottlenecks, and long lead items can, and do, pop up in these subtiers, which can unexpectedly cause no end of problems for their customer companies. As a result, organizations increasingly are adopting software systems that provide multi-enterprise visibility into their supply networks. Often, these systems “scrape” data from multiple enterprise systems, bundle the information into a “data lake,” then create key performance indicators that depict what is happening in supply chains. These systems are like clear glass tubes: Everything coming up from the supply chain is visible, as is the flow of goods to customers downstream. Surprisingly, developing such systems is not as expensive as you might think.

Transparency in contract management can have positive and negative effects as well. The need to communicate transparent evaluation methods early naturally conflicts with the evaluators’ ability to change the relative level of decision criteria importance in a nimble fashion should the agencies’ preferences or needs change after offers are received. It leaves buying teams to formally amend evaluation requirements and extend award and performance start dates, pushing out the timely delivery of agency needs. It can also affect sellers if the agency communicates these new desirable attributes after reviewing proposals, because they may have formed the competitive advantage of a single firm. On the positive side, transparency is the best means for managing post-award performance. Clear, concise, meaningful, and timely performance feedback ensures value to the buying agency and quality and cost improvements for the contractor.

Before and during contract performance, both buyers and suppliers must manage risks. Some are hidden—for example, behavioral risks such as buying agencies changing their interpretations of requirements post-award, or unanticipated geopolitical events. Some are manageable via appropriate contract types, such as cost or price risks for readily available supplies and services. Some risks are expected, but impossible to forecast. Supply chain risk is expected and unpredictable. The best we can hope to do is take strong mitigation and planning steps to prepare for disruptions within the supply system. However, without traceable and transparent supply chains, preparation suffers.

We have seen the devastating effect that opaque and untraceable supply chains can have on crisis response. Almost every major supply chain management organization from the Strategic National Stockpile to individual small businesses has failed to maintain transparent and traceable supply chains in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. We have seen some quick interventions, but most are too little, too late.

Agencies and firms need to be able to “see” and trace their supply chains during national crises. Contractual requirements must be supplemented by inventory visibility systems and blockchain transaction channels. Distributed ledger technology (DLT) such as blockchain creates a trusted network of suppliers through a private and secure technology network. A trusted supplier network allows instantaneous ordering, payment, and notification of receipt. Ideally, DLTs also cure counterfeiting by tracing products’ original country and location.

COVID-19 has revealed how critical it is to be able to track where products are coming from, where they are being sent, and who is receiving them. Pandemic hoarding can be prevented by inventory visibility systems, which employ barcode and QR (quick response) code tracking of material through a supply chain of trusted distributors and manufacturers. Consumption also should be tracked to enable real-time supply allocation decisions based on daily or even hourly updates. Relying on self-reported demand has left the entire world short on life-support materials and services.

Traceability and transparency can reduce the risk of profiteering, counterfeiting, and quality degradation in critical supply chains. Numerous counterfeit and substandard medical products have been delivered to governments around the world. Some governments are not fully accounting for their COVID-19 spending. Recently, for example, the United Kingdom’s Department of Health was challenged for reporting a £3 billion discrepancy in coronavirus contracts not traceable in public records.[3] Blockchain and visibility are critical features, not luxuries, for the future effectiveness of the U.S. Strategic National Stockpile and all healthcare logistics operations.

In his book The LIVING Supply Chain,[4] Rob Handfield addresses the notion that visibility is related to sustainability. If we have transparency, we can develop supply chains with zero emissions and low carbon footprints that do not infringe on labor and human rights. You can’t fix or protect what you can’t see. Supply chains in motion do less harm to the environment, but they require multitier visibility to move quickly. Transparency lends assurance that activities are being performed in the proper fashion. Clear, trustworthy information flows create checks and balances.

Transparency is paramount to both contract management and supply chain management. We couldn’t think of a more important or appropriate topic to kick off this column. We encourage contract and supply managers to make transparency a top priority. CM

Daniel J. Finkenstadt, Maj. (USAF), PhD

- Assistant Professor, Graduate School of Defense Management, Naval Postgraduate School.

Rob Handfield, PhD

- Bank of America University Distinguished Professor of Supply Chain Management, North Carolina State University.

- Director, Supply Chain Resource Cooperative (http://scm.ncsu.edu/).

- Also serves on the Faculty for Operations Research Curriculum, North Carolina State University.

The positions, opinions, and statements in this column are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the official positions of the U.S. Air Force, Department of Defense, or federal government.

Endnotes

[1] Pub. L. 116-92.

[2] Editor’s Note: For more information on the CMS™, visit https://www.ncmahq.org/contract-management-standard.

[3] Dan Bloom, “Tories face legal challenge over £3bn of ‘missing’ coronavirus contracts,” Mirror (October 11, 2020), available at https://www.msn.com/en-gb/news/uknews/tories-face-legal-challenge-over-3bn-of-missing-coronavirus-contracts/ar-BB19ULhw?ocid=msedgntp.

[4] Robert Handfield and Tom Linton, The LIVING Supply Chain: The Evolving Imperative of Operating in Real Time (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2017).