Innovations: What Makes Public Sector Innovation Different

As practitioners and teachers of innovation, we often get asked: How is innovation in the public sector different than in the private sector?

As the innovation imperative spreads across the Department of Defense (DoD) and into civilian agencies, government is looking for the secret sauce that makes private sector innovation so seemingly successful. Geoff Orazem and Peet van Biljon find plenty of similarities between public and private innovation, with differences primarily in speed and, not surprisingly, risk tolerance.

I was particularly struck by their recommendation for more marketing by government. Having once written a column titled “So Many Innovation Hubs, So Hard to Find Them,”[1] I am only too familiar with government’s troubles connecting with innovative companies. As Orazem and van Biljon point out, venture capitalists constantly market themselves to startups.

The 2021 National Defense Authorization Act prods DoD in this direction by requiring the department to publish a list of all its other transaction authority consortia. Run by nonprofits, these entities assemble groups of mostly nontraditional defense suppliers and disseminate to them requests for white papers in response to programs’ solicitations for innovative solutions.

Similarly, the General Services Administration’s (GSA’s) new governmentwide acquisition contract (GWAC), Polaris, is designed to attract small businesses selling innovative technology. GSA points out that Polaris is the guiding star, and its namesake GWAC is designed to guide innovative firms in navigating the market. Orazem and van Biljon serve up plenty more ideas here. Enjoy!

—Anne Laurent, NCMA Director of Professional Practice and Innovation

_________________________________________________________________________

As practitioners and teachers of innovation, we often get asked: How is innovation in the public sector different than in the private sector?

When government managers and workers ask, they almost always have another question on their minds: “How can I successfully innovate in the public sector to overcome the special challenges and constraints at a government agency?” Sometimes, there’s even a hint of an excuse: “You have to understand that it’s tougher for us. We have constraints that they don’t have in the private sector.”

Let’s peel the onion a bit on what really is different; what seems different but is actually quite similar; and what is the same between public and private sector innovation.

Speed and Risk

The major differences between private and public innovation are speed and risk tolerance. Overall, the private and public sectors are similarly risk-tolerant, but how they conceptualize risk and the types of risk each will accept can be quite different.

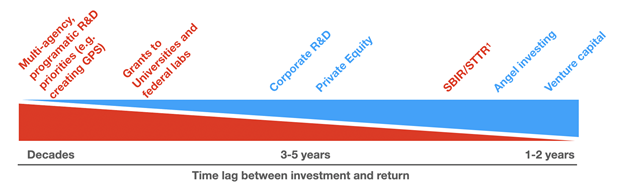

Private companies generally innovate faster but often prefer to make bets on proven technologies that can deliver revenue or other commercial benefits quickly. The public sector usually moves more slowly but is willing to take on higher technology risk and invest in long-term research that could take decades to mature.

Fig.1is an illustration of the time lag between investment and returns for various types of public (red) and private (blue) sector programs. (See FIGURE 1) Table 1 is a comparison of some of the main differences between public and private sector innovation. (See TABLE 1).

Figure 1. Typical Time from Funding to Return for Various Public and Private Programs[i]

Table 1. Comparison Between Public and Private Sector Innovation

| |

Public Sector |

Private Sector |

| Innovation’s purpose & goals |

To better deliver on a public mission

To create/incubate a new sector or industry for the country |

To increase revenue, decrease cost, and thereby drive returns for investors.

Shareholder returns may be supplemented by environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations. |

| Who typically gets funded |

Small

group of universities, large labs, repeat Small Business Innovation

Research (SBIR) winners, and large private companies that focus on

public R&D projects. |

Start-ups: Theoretically everyone with an idea, though in practice women and minority founders struggle.[i]

Established firms: Usually only designated managers who are authorized to apply for approval. |

| What gets funded |

Mission-oriented technology |

B2B and B2C product companies. For example:

Social media products, consumer products, cyber security products |

| Source of funds |

Taxpayers |

Private investors who expect returns. |

| End-user/ funder alignment |

The

end user for the innovation, and the funder of the innovation tend to

be different people in different parts of the organization who don’t

communicate. |

Company innovation teams tend to be well connected to the end user.

External innovation teams (venture capitalists (VCs)s) spend significant time understanding the market and end users. |

| Funding Process |

When:

SBIR and STTR (the principal programs targeting early stage founders)

have annual “solicitation windows,” and if an innovator misses the

window they might have to wait a year or more to compete for funding.

Funds generally lost if not used during fiscal year.[ii]

Finance sequencing: Set funding rounds |

When: Rolling investment rounds for startup with annual and quarterly budget cycles for established firms.

Unused funds automatically available in next fiscal year.

Finance sequencing: Size and volume of startup funding rounds tailored to the investor and inventor’s needs. |

| Risk Tolerance of Investors |

● Open to long-term investments in high-risk technologies

● Do not care about commercial risk (they aren’t trying to profit)

● Expect to see a strong track record |

● Want little to no technical risk that could delay fielding

● Open to some commercial risk if it’s quantifiable

● Open to first-time startup founders |

| Compensating investors for the risk they are taking with their money |

● The government can better deliver on its mission

● National security and prosperity, economic growth |

● Corporate innovation: Increased profitability thanks to the innovation

● VC: Equity in investees |

| Decision process |

In

the SBIR/STTR program applicants have one opportunity to submit a

proposal per cycle and the government makes one decision whether to

fund (black box review process) |

Startups have multiple rounds of pitching, reviews, and revisions.

Established firms have formal phase-gate approval processes to authorize funding for different project stages. |

| Oversight |

Highly

regulated with oversight from many internal and external groups (due

to investment of taxpayer dollars in technologies that can affect

millions of people) |

As loose or regulated as shareholders

and investors choose, subject to external constraints such as stock

exchange rules, corporate law, and antitrust considerations. |

Success Factors

Whether you are innovating in the public or private space some common principles hold true, even if the terminology used is sometimes different.

1. Align with strategy.

All innovation efforts need to fit into and align with the overall strategy of the organization. In the private sector, this might be a particular growth strategy. In the public sector, this is the overarching mission of the agency. Without a strong, easily communicated connection between the proposed innovation and the investor’s goal, the project is unlikely to get management support or funding.

2. Pick growth markets.

Being in the right place at the right time is as important in innovation as in life. In the private sector, picking the hottest sector within a growth market can compensate for many other flaws. For example, the best flip-phone maker will lag an average smartphone maker once consumer preferences have shifted, as Nokia found out to its detriment a decade ago. While not as visible, the public sector has growth markets too. Currently anything related to sensors or hypersonics seems to be getting funding.

3. Allocate resources consistently.

Innovation must be properly resourced, no matter the sector. The Defense Department (DoD) may declare that artificial intelligence (AI) is the future of national security, but actual budget allocations will be a more accurate assessment of DoD priorities.

4. Get differentiated insight.

Truly differentiated insight has three main sources:

● Future consumers and their needs and desires.

○ For example, the government identified that cybersecurity experts were concerned with how quantum computing would affect password-based security and began investing in communities and events to explore the topic.

● Capabilities of current and new technology.

○ The government is the funder for deep tech, for example, the Global Positioning System (GPS), semiconductors, solar power, and the like.

● New business models in similar industries and situations.

○The Air Force and Navy’s Dual-Use SBIR, and both the Defense Innovation Unit and the Air Force’s “Pitch Days” were modeled in part on best practices from private-sector technology accelerators and VCs.

5. Experiment and iterate.

Innovation requires both an organizational culture that enables experimentation culture, and a robust process for quickly prototyping, testing, and learning.

6. Execute with excellence.

Innovation cannot succeed without proper execution, because innovation means building new things and changing the way things are done. Execution gaps are particularly visible in the launch and scale-up phases, but typically reflect mistakes made much earlier in the innovation process—for example, the troubled healthcare.gov launch.

7. Mobilize your organization.

Whether in the private or public sector, successful innovation requires the efforts of many people. It always requires leadership, healthy mechanisms for exchanging knowledge, and collaboration.

Adapting Innovation for the Public Sector

Public sector innovation can be more effective. Here are some suggestions:

● Marketing: Perhaps the single largest opportunity to improve government innovation is to make inventors and entrepreneurs more aware of it. Even the most respected and best-known venture capitalists market themselves and release white papers to attract the best companies. The government has funded some of the most impressive technologies of the last 100 years and has some of the most generous funding terms in the market. However, many innovators don’t know that the government could fund them.

● Differentiate between long-term R&D and innovation: As discussed above, the government is one of the few organizations that still performs long-term research into technologies that won’t go to market for decades. This commitment to deep research is critical and should be protected. However, we recommend that public sector funders be clear about these expectations, so inventors can quickly identify which programs are good for them. For example, founders with an intriguing idea frequently apply to the Dual-Use SBIR, which does not fund early-stage technology (although DARPA, NSF, and HHS love early-stage ideas). This lack of understanding about where founders should go leads to frustration and wasted effort by industry and government.

● Short, deliverables-oriented public innovation: For short-term and more outcomes-oriented innovation (such as the SBIR program) commercial innovation practices are applicable and should be followed. The Air Force and Navy are driving towards this with their short, VC-aligned application processes.

● Connect end users and funders: Requests for proposal and other requests for innovation should be crafted collaboratively with end users to ensure their needs are reflected and in ways that ensure that interested applicants understand what the government wants to fund.

● Connect acquisitions and innovation: Publicly funded innovation is typically planned, budgeted, and run by one group. In the DoD these tend to be service research labs like Army Research Lab or the R&D sponsoring organization. In civilian agencies, it varies but tends to be in a separate, nonoperational team. Generally, a different group, usually the contracting office, handles procurement of the proposed solutions. If the two are coordinated, this should not be a problem. However, in our experience, the two rarely work closely together. As a result, many government-funded solutions die in this transition. To address this, we recommend:

- Separate multiyear budgets for the acquisition of solutions coming out of innovation programs.

- Requiring end users (program offices) to contribute to seed-stage investments made for them (e.g., SBIR Phases I and II).

- Create an indefinite-delivery-indefinite-quantity vehicle (IDIQ) to buy the solutions generated from innovation programs. The annual funding for the IDIQ could be set by looking at the number of solutions expected to mature in the following 12 months, and by looking at the historic innovation success rates. This would create contracting flexibility and agility so that solutions could rapidly transition to traditional contracting.

● Pull-based funding: Commercial investors typically have an area of interest. For example, they invest in cybersecurity or biotechnology. Their focus areas are sufficiently broad, however, that companies with a range of good ideas can approach them and potentially get funded. This balance of specificity to create subject matter expertise with breadth to allow flexibility is critical to both funders and inventors. We recommend that public sector organizations follow this model by outlining the outcome they seek or the broad topic they are interested in without being overly prescriptive.

● Iterative evaluation: Federally funded innovation tends to be heavy on compliance and process. This creates transaction costs on both sides and is an area of improvement. The quick fix is to shift to a more iterative evaluation process so that new applicants who have promising solutions can make multiple attempts at delivering a compliant application when their innovation has merit. For example, in the application process the government could greenlight applicants, reject applicants, or provide feedback and allow inventors to resubmit for immediate reconsideration.

●Focus on business solutions: Historically, we have seen the government fund substantive technology (e.g., material science, biotechnology) but not business process improvements. The government runs one of the largest bureaucracies in the world and could significantly improve delivery by funding and focusing on process improvement solutions.

The United States is in a challenging moment with historic levels of mistrust and discontent among Americans in their own government[ii] and pressure from near-peer competitors in China and Russia. The best way for the nation to meet these challenges is through innovation and bold leadership. Thankfully, the private sector already has established many best practices that government can adapt and follow. Additionally, the private sector and government could work together much more often if the private sector appreciated how the government funds and manages innovation and the government appreciated how the private sector commercializes successes. National innovation is strengthened when the public and private sectors work in tandem, each playing to their own strengths while complementing the other. CM

Geoff Orazem, JD

- Cofounder and managing partner, Eastern Foundry (an incubator for government technology companies)

- Founder of FedScout, a mobile app and platform to make the government market more accessible.

- Frequent speaker and educator on government innovation and funding topics.

Peet van Biljon, MEcon

- Founder, BMNP Strategies, LLC.

- Advises clients on innovation strategy, new product development, R&D transformation.

- Teaches a graduate course on innovation and public policy at McCourt School of Public Policy, Georgetown University.

[i] https://www.fedscout.com/blog?hsLang=en; https://www.sbir.gov/.

[ii] w.pewresearch.org/politics/2020/09/14/americans-views-of-government-low-trust-but-some-positive-performance-ratings/