Don't Just buy American, Build American

Authors: Dan Finkenstadt and Rob Handfield

This special, out-of-sequence Supply Lines discusses a recent Biden administration executive order that will require contracting professionals to collectively reexamine Buy American supplier systems.

On January 20, Joe Biden was inaugurated as president and began signing a flurry of executive orders (EOs) that have major implications for supply chain and contract management. Our focus is EO No. 14005, “Ensuring the Future Is Made in All of America by All of America’s Workers, [i],[ii] signed by Biden as part of his Build Back Better commitment to increase investments in U.S. manufacturing and workers.

Past and current policies have set preferences for purchasing American-made products. To meet today’s global reality, we need to come to grips with the fact that the state of markets for many products (and some services) make American solutions infeasible. Those cases require an approach that bolsters the availability of domestic and Pan-American sources, as well as strategic global sourcing partnerships. We need more than just a “buy” strategy; we need a “build” strategy based on a concept of global independence. To increase domestic production, we must grasp the reality of what 20 years of outsourcing to low-cost economies has done to our economy and the sourcing structure for most products we buy today.

Background: The Buy American Act

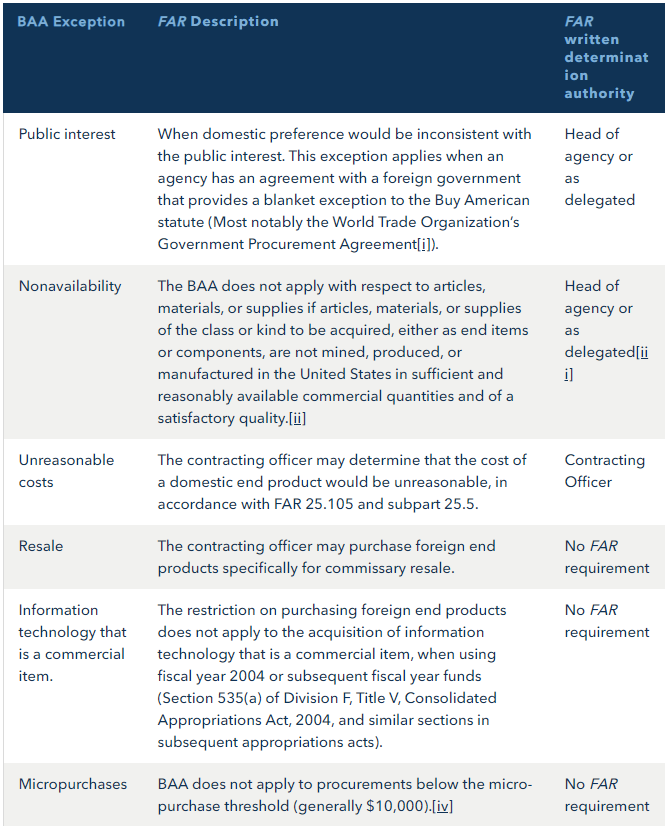

The Buy American Act (BAA)[iii] was first signed into law in 1933 to respond to the Great Depression by restricting public procurement of supplies that are not domestic end products.[iv] End products under the BAA include construction and some products supplied under services contracts. The key aspect of this legislation is its focus on the manufacturing source. For example, American goods sold by a foreign company are still considered domestic, while foreign-manufactured goods sold by an American company are not. There are plenty of exceptions, which are determined by agencies on a case-by-case or blanket basis (See Table 1).

Table 1: Buy American Act Exceptions From Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) Part 25

Recent Buy American and Domestic Resource Policy

In April 2017, then-President Trump signed EO No. 13788, titled “Buy American and Hire Aerican: Putting American Workers First,”[i] mainly focused on enforcing illegal immigration hiring restrictions. It did not address the procurement of American goods or services. President Trump also signed EO No. 13953 in September 2020, titled “Addressing the Threat to the Domestic Supply Chain From Reliance on Critical Minerals From Foreign Adversaries and Supporting the Domestic Mining and Processing Industries.”[ii] This EO sought to increase mining and manufacturing for critical materials necessary to U.S. economic interests. The Trump administration took additional executive action to ban communication applications WeChat and TikTok and their owners as part of a supply chain security initiative in 2020[iii].

Concerns

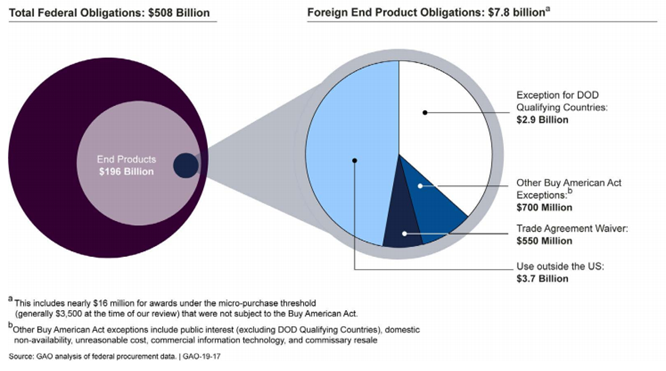

In April 2020, the Trump administration sought to take additional executive action to bolster Buy American provisions. The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) provided a critique of Trump policy citing concern about increasing the Buy American focus amid the constraints and challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. CSIS also noted 2018 Government Accountability Office findings[iv] that, based on current waivers and exceptions, only 5 percent of federal obligations are for foreign end products subject to the BAA. What’s more, many are for defense equipment intended for use outside the U.S. and therefore exempt from the BAA entirely (See Fig. 1)[v].

Figure 1: Foreign End Product Contract Obligations and Associated Exceptions and Waivers, Fiscal year 2017

The GAO report shows that less than 2 percent of foreign goods are purchased via waiver or DoD exception.[i] So, actions to increase the procurement of American-made goods would have to focus elsewhere. CSIS’s main critique is that restricting federal procurement will do little to affect the private market purchasing decisions that overwhelmingly drive manufacturing and supply chain availability in the United States, especially of healthcare and medical supplies and services. The focus on federal procurement also reflects a lack of understanding of global supply chain structures.

Review of the Trump-era EO

The current EO attempts to update domestic preferences by:

- Directing agencies to close current loopholes in how domestic content is measured and increase domestic content requirements;

- Appointing a new senior leader in the Executive Office of the President in charge of the government’s Made-in-America policy approach;

- Increasing oversight of potential waivers to domestic preference laws;

- Connecting new businesses to contracting opportunities by requiring active use of supplier scouting by agencies;

- Reiterating the President’s strong support for the Jones Act;[ii] and

- Directing a cross-agency review of all domestic preferences.

Point 1: Closing loopholes and increasing domestic requirements

This action increases the required domestic manufacturing percentage from 50 to 55 percent (95 percent for iron and steel products) and increases the price evaluation differential for nondomestic product evaluations.[iii] This price differential is not defined within the EO. The order also changes the manufacturing percentage from a component-based test under FAR Part 25 to a total-added-value basis (also not defined).

The primary concern here is that these changes will not increase the availability of critical manufacturing resources. It is hard to imagine how much difference a 5 percent increase in domestic content costs will make in markets where no domestic source exists. In these cases, the government will have to establish other incentives for such sources to manifest. In many cases, entering these markets requires large capital investments and years to establish learning curves strong enough to overcome the vast difference in U.S. versus overseas labor costs. We also must guard against unintended consequences.

For example, if 55 percent of manufacturing component costs must come from U.S. sources, profit-motivated companies could hit the required percentage domestically while still relying on cheap overseas labor and raw materials to offset their total manufacturing costs. However, increasing the percentage could lead to negative downstream impacts to global supplier workforce conditions. Firms could further squeeze overseas labor costs to increase the share of domestic product costs to qualify for BAA. Perhaps the total-added value definition will address this concern, but this remains to be seen.

Assessments of domestic cost contribution should be tied to value in terms of product outcomes as well as production. The key questions should be “Do the components provided by domestic sources overwhelming contribute to its functionality?” and “Does the overall product component sourcing structure minimize the risk of global supply disruption?”

The change to a 55 percent domestic cost threshold would not have solved the shortages of personal protective equipment and medical supplies needed for COVID response. Requiring that 55 percent of component costs be from American sources is a pipe dream for the N95 mask market, for example. Even before 2020, 95 percent of those masks were produced outside the United States. To ensure the government prefers American-made goods and services, the entire product value chain must be assessed for all categories deemed critical to national security (physical, economic, and health).

Rather than focusing goals on product costs, the target should be core components that endanger national security if they run short due to global supply disruption. If nonwoven material is not the most expensive component in manufacturing masks, it doesn’t matter. Without it, manufacturing cannot occur in the first place. So, the goal should be to ensure U.S. access to such keystone components, not simply to ensure 55 percent of manufacturing costs are supplied here.

It also is unclear how procurement personnel are to determine whether a price is so unreasonable as to trigger a BAA exception and choice of an overseas source over a U.S. provider. The overseas vs. domestic difference in labor rates in cost makes price reasonableness determinations hard for most government contracting professionals.

Point 2: Executive Officer for Made-in-America

This action is promising. Gaining top-level buy-in is critical to driving institutional change. However, this role seems quite broad. We recommend the director of Made-in-America at the Office of Management and Budget take a category-management approach to instituting the new BAA enforcement actions. Having a whole-of-government picture will be necessary to implement all other lines of effort under this EO. We recommend that the director work with the Office of Federal Procurement Policy (OFPP) to establish Buy American advocates within each federal spending category and each federal agency to keep abreast of products that are domestically available but not leveraged and to identify critical life-support and -sustainment markets with limited domestic sources of material or manufacturing (e.g., medical supplies, critical food products and plants (such as rubber trees), textiles, rare earth elements, etc.).

Point 3: Increase domestic waiver oversight

We agree that having the General Services Administration (GSA) publish all existing BAA waivers is important. However, the waiver and exception provisions of FAR Part 25 are complex and confusing. We recommend that the Director of Made-in-America and GSA establish a natural-language-processing-enabled application that works similarly to TurboTax. The software would allow procurement personnel to answer a string of basic questions that lead to an indication of “waived,” “exception,” or “no waiver or exception” with an associated link to the appropriate BAA waivers and exception rules. This system could be updated in real-time to ensure that only current waivers and exceptions are considered.

Waiver overseers should acknowledge that for certain industries, re-shoring is unlikely ever to happen. The costs of transferring an entire industry are too great, and no entity is likely to take on the investment risks knowing full well that it never will be competitive with less expensive, entrenched foreign suppliers.

Point 4: Supplier Scouting

This is a very promising directive. Essentially, it requires the use of robust and persistent market intelligence to enable agencies to become aware of nascent or opaque domestic sources of manufacturing via the Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP)[iv] in all 50 states and Puerto Rico. We again recommend the use of category management and coordination with OFPP as the best first steps for organizing this effort. We have previously written about the concept of orbital market intelligence to stay abreast of sourcing solutions.[v] We further recommend that the director of Made-in-America consider manufacturing capabilities incubated, grown, and advanced by the U.S. university system (e.g., advanced textile manufacturing capabilities at the Wilson College of Textiles at North Carolina State University, which responded in the early months of the pandemic with much-needed nonwoven materials).

Point 5: Support for the Jones Act

Though the White House summary states that support for the Jones Act is a critical feature of the recent EO, it is only mentioned once to clarify that it qualifies as a Made-in-America for domestic preference. The Jones Act regulates maritime commerce in the United States. It requires goods shipped between U.S. ports to be transported on ships that are built, owned, and operated by United States citizens or permanent residents. We agree the Jones Act should continue to be supported, but do not see how it is considered a central feature of this EO.

Point 6: Cross-agency review of domestic preference

The concept of biannual reviews for potential domestic service and manufacturing opportunities seems reasonable. The EO calls for updates to the list of nonavailable articles at FAR section 25.104(a) and a prompt review (“prompt” is not clearly defined) of information technology that qualifies as a commercial item. We encourage these reviews to consider how requirements are developed and defined.

Demand management and requirements development are cornerstones of sound category management. Coupled with strong market intelligence, demand management can lead to novel solutions that can open areas of innovation that increase the availability of domestic sources. For example, as part of a Hacking for Defense[vi] project, a team of MBA students at the Naval Postgraduate School recently presented Army Futures Command with a set of novel solutions to aid in developing a strategy for advanced textiles. The students mapped the textile manufacturing value chain, identified the scope of textile products used by the Army, and surveyed existing and developmental automation and robotic assembly technologies. The effort included recommendations on the use of 3-D printing and nascent cut-and-sew automation to increase opportunities for domestic sourcing to meet Army needs. Such projects should be scaled across multiple federal spending categories to identify new or emerging Buy American opportunities.

Additionally, the PPE industry has high potential for domestic growth due to the existence of a textiles industry in the Southeast United States that is ready to adapt to nonwoven materials and mask production. Though much of the manufacturing had moved overseas, the necessary infrastructure, technical knowledge, skills, and abilities still remain within the local population and university system of states like North Carolina. Further, the United States has significant pharmaceutical and biotech production already and has potential for growth.

Government engineering staff should take care to seek and apply industrywide specifications to maximize the likelihood that domestic manufacturers serve the larger market and do not become overly reliant on federal buyers.

Final Recommendations

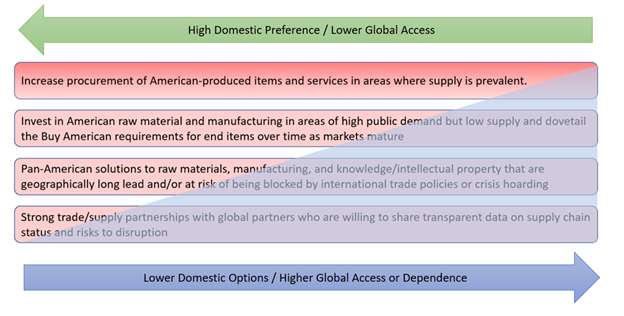

The Biden administration’s early push for improving Buy American policy is encouraging, but it needs further development. We offer the following top-level recommendations, intended to play off one another to develop domestic availability for critical products and services within the public procurement portfolio (See Fig. 2).

- Increase procurement of American-produced items and services in areas where supply is prevalent. Despite some myopia, the EO ideal of encouraging more Made-in-America products still is a noble endeavor. Focus on high-tech areas wherein protecting intellectual property (IP) is critical.

- Invest in American raw materials and manufacturing in high public demand but low supply. At the same time, focus Buy American requirements on end items for which we need to build domestic capacity over time as markets mature.

- Work toward a strategy of global independence. Look to Pan-American sources for products and raw materials that currently come from other suppliers with long production cycles and/or that are geographically distant from the United States whose supply could be blocked by international trade policies or hoarding during global emergencies.

- Under the same global independence strategy, develop strong trade/supply partnerships with global partners who are willing to share transparent data on supply chain status and risks using safer and stronger technologies such as distributed ledgers.

Figure 2: Build American Public Procurement Dovetail Strategy for U.S. Supply Chain Global Independence.

Final thought: Don’t put the Buy American status decision on individual buyers or contracting officers. Elevate that determination and develop approved supplier systems for each federal spending category managed under this initiative. Make these systems accessible to all public procurement personnel and requirement developers. Allow emerging solutions to be added to create not just a Buy American strategy, but a Build American one. CM

*Disclaimer: The positions, opinions and statements in this column are those of the authors and do not reflect the official positions of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense or Federal Government.

Daniel J. Finkenstadt, Maj. (USAF), PhD

- Assistant Professor, Graduate School of Defense Management, Naval Postgraduate School.

Rob Handfield, PhD

- Bank of America University Distinguished Professor of Supply Chain Management, North Carolina State University.

- Director, Supply Chain Resource Cooperative (http://scm.ncsu.edu/).

- Also serves on the Faculty for Operations Research Curriculum, North Carolina State University.

[1] 86 FR 7475; see Executive Order on Ensuring the Future Is Made in All of America by All of America's Workers | The White House

[1] Pub.L. 72–428.

[1] GAO-19-17, Buy American Act: Actions Needed to Improve Exception and Waiver Reporting and Selected Agency Guidance, Government Accountability Office, December 2018, accessible at https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/696086.pdf

[1] The WTO GPA provides for the U.S. and other GPA countries to compete foreign and domestic products on equal footing without the cost evaluation offsets prescribed by the FAR or similar foreign country regulations. An expansive list of WTO GPA and other trade agreement eligible criteria, evaluation concerns and thresholds can be found at FAR 25.4.

[1] Note: This can include that domestic sources can only meet 50 percent or less of total U.S. government and nongovernment demand per FAR 25.103(b)(1)(i).

[1] Note: Federal-level class determinations for products deemed as nonavailable can be found at FAR 25.104 and are updated every five years.

[1] Note: The micropurchase thresholds can be found at FAR Part 2 and include certain exceptions such as construction ($2,000), services ($2,500), domestic contingencies ($20,000) and contingencies abroad ($35,000).

[1] 82 FR 18837.

[1] 85 FR 62539.

[1] Executive Order No. 13942, “Addressing the Threat Posed by TikTok, and Taking Additional Steps to Address the National Emergency With Respect to the Information and Communications Technology and Services Supply Chain” (85 FR 48637). https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/08/11/2020-17699/addressing-the-threat-posed-by-tiktok-and-taking-additional-steps-to-address-the-national-emergency.

[1] GAO-19-17.

[1] William Alan Renisch and Jack Caporal, “A World in Crisis: Will Buying American Help or Hurt?” Center for Strategic and International Studies, April 10, 2020, https://www.csis.org/analysis/world-crisis-will-buying-american-help-or-hurt

[1] ($2.9M DoD qualifying countries + $700K granted exceptions)/$196M end product total = 1.84 percent or roughly 2 percent as reported by CSIS.

[1] Merchant Marine Act of 1920; Pub.L. 66–261

[1] Ellyn Ferguson, “Biden turns to ‘Buy American’ law to aid US manufacturing,” Roll Call, January 25, 2021,

https://www.rollcall.com/2021/01/25/biden-turns-to-buy-american-law-to-aid-us-manufacturing/

[1] The Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP) at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) provides the federal government funding for the MEP National Network™. The MEP National Network makes up the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s Manufacturing Extension Partnership (NIST MEP). There are 51 MEP Centers located in all 50 states and Puerto Rico, with over 1,400 trusted advisors and experts at more than 385 MEP service locations. The MEP seeks to provide any U.S. manufacturer with access to resources needed to succeed. https://www.nist.gov/mep/about-nist-mep.

[1] Robert Handfield, Daniel Joseph Finkenstadt, Eugene S. Schneller, A. Blanton Godfrey, and Peter Guinto, “A Commons for a Supply Chain in the Post‐COVID‐19 Era: The Case for a Reformed Strategic National Stockpile,” The Milbank Quarterly 98, no. 4 (2020), 1058-1090. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12485 (See Orbital Market Intelligence Web Appendix).

[1] https://www.h4d.us/ .