How Emerging Technology is Advancing Good Government

DHS’ Procurement Innovation Lab, along with its partners and vendors, is getting the government’s AI ball rolling by taking aim at contractor past performance data.

BY SCOTT SIMPSON AND POLLY HALL

Across the federal government, bots and artificial intelligence (AI) are springing up to augment and assist acquisition professionals. This often makes people think of a futuristic sci-fi setting, but the truth is even more exciting!

Imagine a world where government and industry work together to create a new product that transforms the way federal contracting professionals can access and interact with data, aiding them as they execute the procurement process. That world is happening now—it is the reality of the Artificial Intelligence for Past Performance Project.

The President’s Management Agenda[1] established goals of increasing the use of automation software to improve the efficiency of government services as well as leveraging government data as a strategic asset. In 2019, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Procurement Innovation Lab (PIL) led an acquisition modernization pilot in collaboration with the Office of Federal Procurement Policy (OFPP) and the Chief Acquisition Officers’ Council (CAOC). Through DHS reverse industry days and acquisition innovation roundtables, industry shared the challenges it sees with using the Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System (CPARS)—e.g., poor data quality and acquisition teams not using the system. These collective challenges were a catalyst for change, and DHS’ Chief Procurement Officer, Soraya Correa, acted. Based on her own experience with CPARS and industry’s concerns, she shared the idea of exploring AI to improve the CPARS user experience with OFPP, who was excited to partner on the endeavor.

DHS then inquired with those working on the front lines of contracting to determine how they thought automation and emerging technology could help improve the acquisition process. Through engagement with the Front Line Forum, a group representing operational contracting officers across the federal government, and a survey conducted by OFPP, a consistent theme emerged: Three out of four acquisition professionals identified the past performance evaluation process as an opportunity for intelligent automation to support the workforce.

CPARS has a wealth of data, with over 1 million records for over 60,000 vendors, but it is hard to rapidly access assessment reports that are relevant to a given source selection. One company might have contracts to support the Department of Defense (DOD) for weapon systems, DHS for cybersecurity, and Veterans Affairs (VA) for information systems, with multiple years of performance. In this scenario, the report results are voluminous. There is no efficient way for a human to easily review them all. When a contracting officer queries CPARS to perform a source selection evaluation on that company, all the information is presented together. It is difficult to manually review each record and synthesize the information to get an overall picture of the contractor’s past performance. This process is time consuming, leads to frustration, and results in using workarounds, such as distributing a past performance questionnaire. By using a questionnaire, the acquisition professional relinquishes the responsibility of identifying relevant past performance information to vendors.

Given the user experience, DHS now had a challenge for industry: How could emerging technology, such as machine learning and AI, help federal contracting professionals rapidly access relevant records from CPARS for a given source selection; and could it provide adequate insight into the data to aid in the review and evaluation of a vendor’s past performance?

Their answer? Yes. Enter commercial artificial intelligence and intelligent automation.

Creating New Commercial Solutions to Support Acquisition Modernization

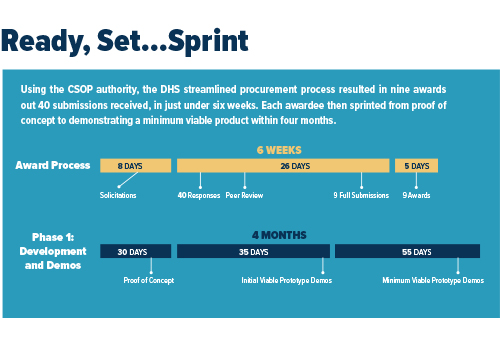

DHS used the Commercial Solutions Opening Pilot Program (CSOP) to award contracts for prototyping and piloting commercial solutions for Artificial Intelligence for Past Performance, which is often referred to as the CPARS AI initiative. The CSOP is a non-Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR)–based authority, granted to DHS under the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2017,[2] which vests contracting officers with procedural discretion and flexibility to buy innovative commercial products through a competitive, merit-based process. This procurement authority allows the procurement process to be streamlined. DHS issued a short, peer-reviewed technical questionnaire; reserved the right to have phone calls with offerors; and used a rapid award process for the selected solutions. With support from OFPP and CAOC, and in collaboration with the DHS Office of the Chief Information Officer (OCIO), the PIL made nine awards out of 40 submissions received in just six weeks. (Refer to FIGURE 1.)

One of the main goals of the Artificial Intelligence for Past Performance Project is to create a commercial marketplace, similar to the credit report marketplace. An agency will be able to purchase past performance reports via a subscription-based service from several different companies, with visual dashboards that provide CPARS users enhanced access to the data so they can analyze it more efficiently and effectively. With this goal in mind, each of the nine CPARS AI awardees received $50,000 and obtained private investment funding to support the development of their prototypes—one of the many flexibilities offered by the CSOP procurement authority.

Iterative Design Using Agile Methodology

A core principle of the Artificial Intelligence for Past Performance Project is that it needs to be executed using an agile development methodology. With this in mind, the CPARS AI project was designed in phases—from prototyping, to piloting, to full production contracts—which allowed for faster learning, obtaining the necessary government buy-in and related policy changes along the way, and saving the taxpayer money. Phase 1 was a four-month sprint with checkpoints for feedback at regular intervals of 30–45 days. These checkpoints throughout the design and development phases ensured that CPARS AI contractors heard multiple perspectives from across the acquisition community. For example, at the first checkpoint, one of the firms had completely misinterpreted a requirement. By providing that early feedback the firm was able to pivot and get its project on the right track.

However, agile doesn’t magically return results—it requires the federal government to engage differently with contractors. The government designated a committed CPARS AI product owner and provided access to data, users, and resources consistently along the way. The first step in ensuring the CPARS AI contractors had the resources they needed was gathering a group of experienced acquisition professionals and CPARS users from across the federal government. Over 100 volunteers responded to the call, sharing their time, experiences, and knowledge to support the design and development of the CPARS AI prototypes. This included simple information (e.g., what they use CPARS for and how long it takes to conduct evaluations) as well as how they thought AI could improve this process. It also included a lot of feedback on product iterations.

Two core principles of the agile methodology are to develop a usable product at every sprint and to obtain feedback on the product so it can be improved quickly. Committed volunteers participated in hours of discovery sessions, design sessions, and demos to ensure each iteration was delivering useful functionality. They also provided constructive feedback to the CPARS AI contractors, and in turn this feedback was used on the next iteration. In short, these volunteers ensured the solutions being developed would work for them!

Using an agile approach also meant being available at every stage—regularly participating in sprint ceremonies, planning sessions, and demonstrations. It was imperative for the DHS PIL, as the product owner, to be available to all nine CPARS AI contractors while also recruiting volunteers, arranging user feedback sessions, preparing more CPARS test data, and managing other job commitments. It also meant answering questions in a timely manner. When operating under a two-week sprint cycle, delaying answers impacts what can be developed under that iteration.

The results speak for themselves—seven of the nine CPARS AI contractors successfully built and demonstrated minimum viable products (MVPs) within four months of the initial CSOP award. This demonstrated the potential of emerging technology to assist the federal government with a long-standing issue and of the value of properly executed agile development approaches.

Lessons Learned

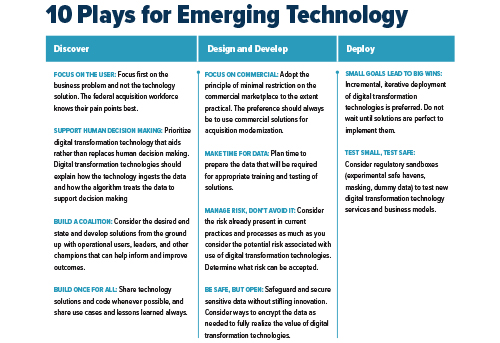

One of the core tenets of the DHS PIL is not only testing new ideas but sharing the results. Therefore, the PIL documented its lessons learned and developed 10 “plays” (see FIGURE 2.) to help other federal programs approach emerging technology, as well as leverage different government data sets more robustly, through the lens of agile methodology.

One of the many lessons learned from the project’s first phase is about the power of CPARS data and how it is used within the current policy. During almost all the user feedback sessions, contracting professionals raised the desire to have the CPARS AI assist with market research. Think about it: There is a wealth of data within CPARS that is not only about how well vendors performed on contract requirements, but which vendors performed those requirements. This is an area that may perhaps warrant further discussion and exploration, but for now the PIL is focused on creating an efficient approach to using the CPARS data to fulfill its original intent: providing past performance information.

The PIL recognized early on that applying AI to the CPARS system was not an easy feat, and success would depend on the efforts of many across the federal government. In addition to OFPP and CAOC, other partners include the Procurement Committee for E-Government and the General Services Administration’s Integrated Award Environment (IAE)—the office that oversees the CPARS. The PIL also realized it would need support to ensure it was implementing the right technology and applying the technology correctly, so it also partnered with DHS OCIO as well as leading AI researchers from the DHS Academic Center of Excellence, Center for Accelerating Operational Efficiency. Finally, and most important, DHS is committed to hearing the voice of the users, the federal acquisition workforce, as the PIL continues to build solutions with them. It was important to establish these relationships early so that all stakeholders were involved in the development process, providing feedback, addressing questions and concerns in real time, and ultimately having confidence in the final solutions.

What’s Next?

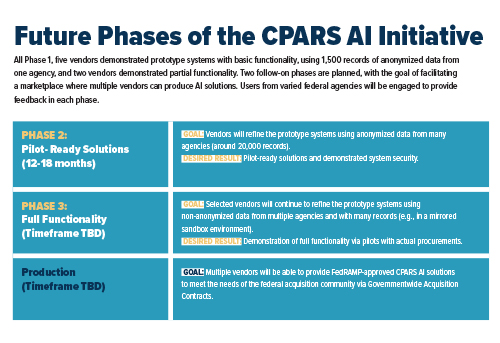

The Artificial Intelligence for Past Performance Project was broken up into several phases. (Refer to FIGURE 3.) Phase 1, “Proof of Concept and Prototyping,” was completed at the end of January 2020 with the successful demonstration of MVPs. Phase 2 will focus on prototype refinement to ensure solutions are ready to pilot in Phase 3. Phase 2, scheduled to kick off in the fall of 2020, will test and refine the MVP solutions, focusing not only on functionality but on the security of the solutions, with the requirement to obtain FedRAMP accreditation prior to piloting in Phase 3. The end vision for this solution comprises commercially available solutions that have FedRAMP authority to operate (ATO) and are available from multiple companies on governmentwide contracts so any federal agency can easily acquire the solutions to aid acquisition teams with efficient past performance evaluations.

The Artificial Intelligence for Past Performance Project is well underway, and this is really an exciting time for the federal acquisition community. The hope is that past performance will become stronger, more differentiating evaluation criteria, not just a process, and that the wealth of data stored within the CPARS can be unleashed to assist with better decision making and better outcomes, improving the federal acquisition community’s ability to do the work that needs to be done! CM

Scott Simpson

- Procurement Innovation Coach (now, “Agile Scrum Convert”).

Polly Hall

- Director, Procurement Innovation Lab, Office of the Chief Procurement Officer, U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

The views presented in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. government.

Endnotes

[1] See, generally, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/management/pma/.